- Apr 16, 2025

Sadhu Stories part 5: My Guru

They say there are three things you must do for your Guru:

Find him.

Love him.

Leave him.

I came to the Kumba Mela armed. My head covered in chainmail, each interlocking ring forged from years of steeling as a critical thinker, tampered by the fire of my intellect, and the hammer of ‘healthy skepticism’. My mind has been trained to question, to look out for inconsistencies, and to never ever take anything at face value. My heart tenderized by a mallet made of loss and betrayal that has beaten it so hard, I wore an kind of invisible bullet-proof vest stitched from past pain and disappointments, designed to absorb against the impact of ever getting hurt again.

Meeting my Guru did not instantly shatter my armor, it wasn’t anything like that, no lighting strike instantly igniting devotion in me.

Instead, it started with that glimpse of something that is impossible to explain; a twinkle in his eyes, a recognition of a shared spiritual connection that I’ve only ever experienced once before, which got me curious of what it all really meant.

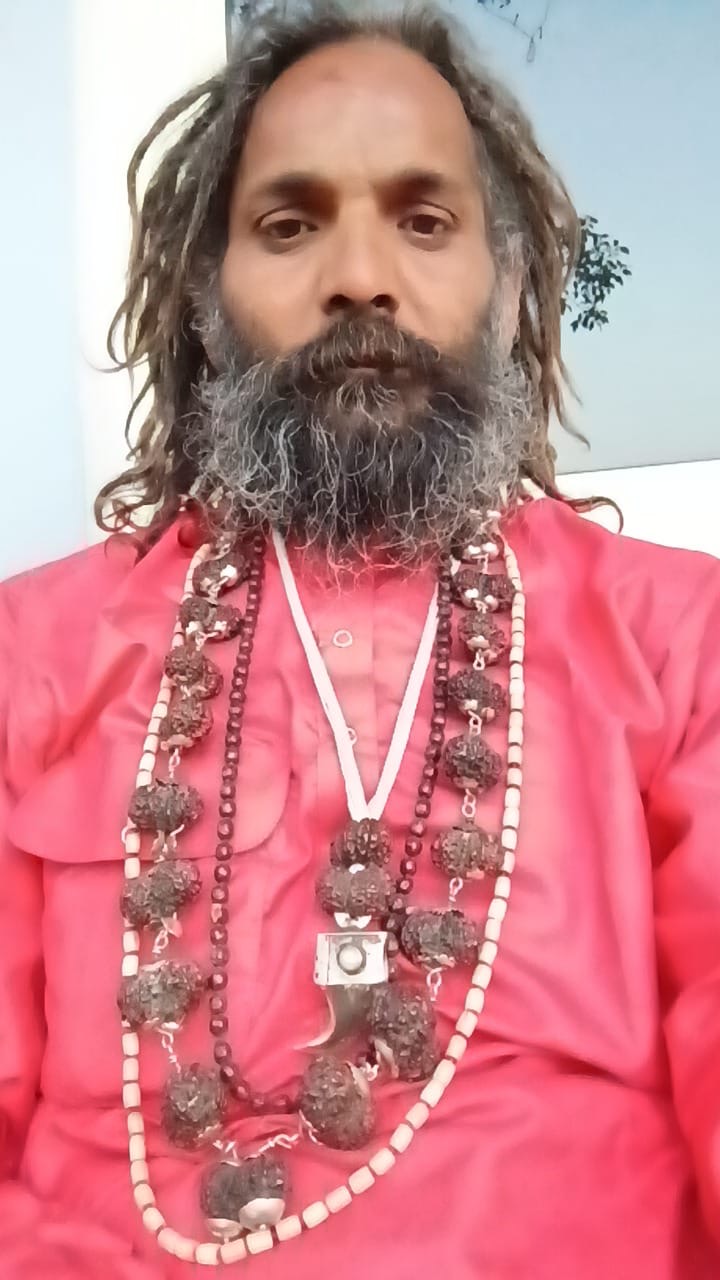

While we were at the Kumba Mela in Prayagraj, Rakesh Giri, the man I began calling my Guru, wore clothes. Like many of the other Sadhus, he wore an orange kurta and matching long dhoti wrapped around his thin waist, and his trusted leopard-print waistcoat, like a wearable version of Hermione’s enchanted bottomless bag, full of of pockets and secret stashes, specially made for him by a tailor in the city and worn threadbare in places, which only emphasized its magical ability to hold so many things without breaking. He also wore heavy rudrakshas around his neck, not the small ones you’re probably used to seeing, but the more rare, huge (at least 3cm in diameter) silver plated double-seeds, fused together in perfect duality that represents the sacred union of the Shiv-Shakti.

His favorite talisman is a tigers’ claw encased in silver crowned with a single perfect pearl. Only Gurus from the most prominent Akhadas can wear these, as it is illegal for regular folk to own or wear tiger parts as they are a protected species. He wore rings on every finger, on some fingers more than two, and as a constant companion, the colorful Baba bag that is a fashion staple for all wandering Sadhus.

He has shoulder length dreads, which is actually quite unusual for someone of his status, as most others who have been Sadhus as long as him have dreads long enough that they hang down to the floor, or even longer. When I asked him why his are so short, he told me sometimes shaves his head because he gets very itchy eczema that really bothers him when it gets really cold in his cave. His Sadhu style is complete with five brown teeth (now four after his last front tooth finally fell out about two weeks ago).

I wonder when you see him if you think just like me, that he looks pretty cool and stylish, he has a powerful presence, commanding respect, and looks a bit like a rockstar, especially when he puts on his favorite pair of shades.

When we got to Varanasi, we first walked down to Man Mandir Ghat, one of the most significant ghats along the Ganges, built in 1600 CE, where some of his Chelas had already set up camp. This is a very busy place, crowded with shops and fronted with wooden platforms where pundits hold pujas from sunrise to sunset, and thousands of people take their holy baths.

His Chelas had brought the big banner with his picture and name on it from Prayagraj, strapped it across their makeshift tent, and we sat down under it to smoke with them. Rakesh Giri told them that in two days he will start making his own space nearby.

The first two nights we stayed in the basement of a hotel that belongs to one of his devotees, a large room that filled up with people at night, sleeping on thin mattresses on the floor. Rakesh Giri and me got the only high beds, where I gratefully slept after ten days on the hard earth in the tent. I spent about twenty minutes in the hot shower that first day. We locked away our backpacks in cupboards where they stayed for the duration of our month in Varanasi.

(Roaming with Rakesh Giri Baba and Masta Giri Baba in Varanasi)

During these first days, we went to eat together, him and me, at Mona Lisa restaurant, one of the oldest roof top restaurants in the city. I found it quite entertaining to see my Guru in such a different context.

One of these times, a British couple came and sat down at the table next to us. They were playing UNO and started talking to me, ignoring Rakesh Giri at first. The man was asking me how I was coping with the chaos, and told us that he’d lost it yesterday walking down the narrow crowded lanes being honked at incessantly by motorbikes. He said he had started shouting for everyone to “shut the fuck up!”. Rakesh Giri found this hilarious and giggled while trying to peer at the mans hand of cards and asked some questions to figure out how the game was played.

I was wondering to myself why these people were here, as they seemed so out of place, simultaneously both ignorant and very judgmental of everything happening around them. I explained that this was my Guru and that he was about to put his tent up down by the ghats like so many of the other Sadhus had already done. I wish I would have recorded the conversation that followed as this very English couple tried to make sense of him, more skeptical and close-minded than I have ever been.

It would have been hilarious for you to see their faces when some friends and followers came to join us, entering the restaurant bowing deeply and touching Rakesh Giri’s feet, his status suddenly shifting from a funny little toothless brown man to an actual real-life Guru sitting there next to them wanting to learn how to play UNO.

And then the true power of the Sadhu started showing itself as the project of setting up his new tent began.

When we first came down to ‘his place’, the chosen corner below the walls of the Brijrama Palace, (a five star hotel built in 1812, with room rates from $540 per night), it was full of hawkers selling chai, fruits, beads, a barber and a man with a stack of with those long candle tubes that pull out your earwax.

Rakesh Giri immediately had his ears cleaned, and then started shouting and screaming at everyone to get out of his space. This was always his spot he told me, this is where he first came with his Guru for his first Kumba Mela.

He first got the cleaners from the five-star hotel to come sweep this chosen area (the contrast between the austere lives of the home-free Sadhus and their makeshift tents that just appeared there, and the luxury five star hotel, is just one of those things that is totally normal in India).

Once clean enough to meet his preference, he unceremoniously sat down on the one-meter wide ledge at the base of the place. Apart from taking trips to the toilet, his daily bath in the Ganges, and when he ran around screaming, shouting, brandishing his sword, hitting the ‘bad’ people, and urging the congregations of pilgrims to keep moving, he sat (and slept) in that exact spot for the next four weeks.

On the other side of his place was a round cement pylon where a small Sadhu they called “Kala Baba” (‘black baba’, because of his very dark skin) had been sitting for months. He invited us over and served his favorite sugary milky coffee which he much prefers over chai, prepared over his little fire in the center.

I liked this baba and took to calling him “Chota Baba” (which means small and felt much kinder than Kala as Indians tend to have a preference for lighter skin).

Rakesh Giri told me that after the end of this Kumb, Chota Baba had promised to join him as his Chela, because he had never had a Guru, meaning he was not part of any Akhada, existing as an outsider of the system.

(Chota Baba in Varanasi)

This freedom of being his own man had suited Chota Baba for many years, but as he was now getting older, from what I understood, he wanted to join the ‘system’ to have more protection.

I sat up so late enjoying the people and conversations at Chota Babas fire one night, that I ended up falling asleep there, out in the open and we shared a beautiful sunrise together the next morning.

Magic started manifesting.

Rakesh Giri had now claimed his space, and piece by piece, his new camp started materializing.

Long bamboo poles for the base, and then a massive piece of yellow tarp appeared to create the new ‘tent’. A captain from one of the many boats that ferry tourists up and down the ghats brought a very pretty embroidered image of Shiva and Shakti with lots of sequins in a heavy wooden frame that was placed on the back wall, creating the backdrop of an altar.

Cooking pots, plates, food and wood for the fire came, seemingly out of ‘nowhere’.

After about two weeks when the mid-day heat had risen to unbearable temperatures for Rakesh Giri who is used to the colder temperatures in the high mountains, and a man brought an electric fan, which was plugged into a multi-socket that someone else had hooked up to to a lamppost, in that ‘how is this possibly safe’ kind of way that holds together so much of Indias electrical wires.

I didn’t see who made the fire pit, but one morning when I came down, it was already there, complete with a huge copper trident shoved into it. One man paid the flower wallah to come place fresh flowers around the fire and hang new garlands over the trident every morning.

After about a week of sitting, we had two swords, a mosquito net tent, several Persian rugs and carpets to sit on, and all manner of gifts in the form of five kg bags of flour (for chapatis), all manner of prasadh, sweets, jewelry, watches, peacock feather wands for giving blessings.

Every day, new things came.

Rakesh Giri sat patiently most of the time, blessing those who came seeking, but there were also moments when he shouted, threw the iron fire poker at people who broke the ‘no photo’ rule, or ran around with his sword to keep the steady stream of passing people moving. It was not allowed for people to sit down on the steps in front of his tent, nor could they use is tent to as a drying rack for their wet clothes after their sacred baths in the Ganges.

The other Sadhus followed his example, and sometimes when we shouted at another person trying to sneak a photo and the person tried to do it anyway, Sadhus from the other tents would sneak up behind them and hit them with their peacock feather wands or swords or fire pokers, which seemed to be the weapons of choice.

Tired pilgrims who tried to sit down for a moments respite where expelled without compassion, even the really old wrinkled men and women who came carrying heavy bags on their heads were smacked and shouted at if they sat down for more than a minute. I was explained that if people were allowed to stop, the whole area would soon become overcrowded.

In so many ways, the Sadhus do a lot to keep things in their territory organized in a way that India really isn’t. They are quite messy, but within their own world, they are quite obsessed about cleanliness, and there are a lot of rules for how to maintain a sacred space. The Sadhus call it ‘bamboo massage’ when they hit people, which I think comes from the lathis (bamboo sticks) that the Indian police often carry and use to hit troublemakers, probably with less discernment than the Sadhus.

The city’s paid street sweepers came a few times a day, but Rakesh Giri also swept the cobble stones in and around his ‘tent’ at least once each morning. I was amazed by how much energy he invested and recognized just how much work and attention was required to keep his territory clean and energetically protected.

A bigger group from the Avana Akhada came a few days after we arrived, and swooped in to take over Chota Babas spot on the pylon in front of us, pushing him over to the side.

(Chota Baba after the Avana Akhada came and took over his spot)

I stopped going to sit with him then, partly because Rakesh Giri asked me not to, and also because some of those Sadhus seemed like greedy posers to me (literally happy to pose for pics as long as they got paid).

Chota Baba would wave at me happily from across the crowds, and put his hands over his head in salutations, and occasionally he’d come over with a cup of coffee, and a few times I went to give him buffalo milk which was his preference, a packet of Gold Flake for his chilium, or his favorite chocolate chip Tiger biscuits. I felt sorry for Chota Baba at first, but then one day I saw he had shaved off all his reads and that got Rakesh Giri absolutely furious.

As it turns out, Chota Baba had signed up with his occupiers instead of with Rakesh Giri as promised; “Liar, cheater and fraudy that Chota Kala Baba!” he yelled brandishing his sword and making threats about bamboo massage, his anger had him talking about nothing else for the rest of the day, although eventually he got over it and moved on to other topics of conversation.

The third day of us sitting there, a big change happened. We all felt the shift in energy that day, there were a lot of ‘bad energy’ people around, like the air was heavier somehow. I had gone roaming and a random man grabbed me by the arm and violently tried to force me into the frame for a selfie. By now I was in full Sadhu-power mode and pushed him away from me shouting in defense of myself: ’ MADACHUT, CHUHO MAT, MAIN MATAJI HOON!’ (which roughly translates as ‘MOTHERFUCKER, DONT TOUCH ME, I AM A HOLY WOMAN!).

Honestly, sometimes India really brings a whole other beast out of me.

Rakesh Giri is vigilant against ‘Liars, cheaters, theirs and fraudies’ entering his space. He also doesn’t allow photos to be taken, which meant a constant vigilance in a crowd armed with mobile phones and total fascination for anything different.

While I think it was a combination of many things, one man in particular seemed to have set him off, or at least he was the one that got on the receiving end; a skinny old mala-wallah who kept inching his blanket of goods further and further to get back to the spot he’d in been before Rakesh Giri turned up to set up camp, right in front of the entrance to his tent, but to be honest I am not quite sure exactly what it was that triggered this massive explosion of anger.

He got up, and was screaming and shouting and hitting this mala-wallah, picked up a bucket of Ganga water, threw it all over the man and his wares, and then came stomping back into the tent, eyes ablaze, and shouting and endless stream of profanities in Hindi. He angrily tore off all his clothes and stripped down fully naked, throwing his precious rudraksha malas, rings and watches (he was wearing three around his left wrist at this time) at me, grabbed his sword and ran over to the neighboring camp of Naga Babas where he got the special powder, rubbed it all over himself until he was totally white.

Looking like a terrifying demonic ghost version of himself, he came back to stand outside the front of his tent, wrapped his penis around the sword, and then stepped over it so the sword was sticking out horizontally behind his butt, holding onto it with one hand on each end, began to squat up and down on the sword, all the while screaming and shouting abuse at everyone present.

Sometimes naked, sometimes mad.

At this point, I had seen so many naked white dust-covered men that it wasn’t as shocking to me as it could have been, but I would be lying if I said it wasn’t one of the weirdest things I’ve seen happen right in front of me.

For the rest of the three and a half weeks we stayed in Varanasi, Rakesh Giri remained a Naga Baba, and eventually I got completely used to this version of him.

When it was cold at night, he’d wrap himself in his orange wool blanket by the fire, but until the last day when we left, he would start each day with a bath in the Ganges and then coat every part of his wet body, including his head, in the white powder, stand in the sun, windmilling his arms and shaking his legs, looking every part the crazed Yogi, until the powder dried on his skin.

I have wondered if I would have felt the same way towards him if he had been a Naga Baba when we first met. It was like suddenly, from being this sort of ‘sane’, rational Sadhu, that I had projected onto him, he set himself free from all such constraints and perceptions, showing up as this totally shameless, uncivilized, wild savage.

After this powerful enraged exhibitionism, our tent filled up with people bowing deeply in reverence.

(Rakesh Giri Baba sitting as Naga Baba)

More than once when I was there, another Baba came (sometimes naked just like him, sometimes wearing clothes) and pulled on Rakesh Girls penis as their way of greeting. From what I could understand, this is a gesture to test their commitment.

When women devotees came complaining over not being able to get pregnant, asking for his help and blessings, he would ask them for one their silver or gold rings (nothing less was acceptable as an offering) and when they handed it over, he would thread it over his penis and announce that now the curse was lifted as they had consecrated the Shiva lingam.

One day ended with three such rings around his penis. That evening as he pulled them off he put them into my hands, and told me to put with all his other treasures into my bag for safekeeping.

Are you shocked yet? At this point, I was so immersed, I mostly found it funny and accepted the ways of the world I was now living in.

Meanwhile, my body kept getting sicker, and about a week after arriving in Varanasi, as me and the others who had been in Prayagraj coughed black and brown gloop, sometimes coughing so much we puked, I broke out in a high fever, and my mind started freaking out with delirious fears that I had caught dengue again (dengue, and jellyfish, are my two biggest fears). I was sent to the doctor who diagnosed me with bronchitis, put me on IV (the male nurse there treated me with so much kindness I cried like a child with relief) and proscribed me heavy duty antibiotics, and warned me to take care or I’d end up with pneumonia.

The next afternoon as I felt better, Rakesh Giri started getting sicker. That must have been a funny moment if you had been there, because I actually shouted at him to take his medicine when he refused, at one point screaming in his face that “I am not going to follow a sick Guru, I want my Guru healthy, shut up and eat your own medicine!!”

After this, I gave up on sleeping outside in the dirty air and constant crowds, and rented a room with AC in a hotel for myself, but as soon as I got better spent most of my time down at the ghats anyway, partly because I felt like thats why I was there, partly because Rakesh Giri wanted me to, and partly because there wasn’t much else to do.

I met some Rainbow-ers and other trippy hippies, but I didn’t feel like I resonated with them at this time, didn’t enjoy their conversations, instead preferring to sit next to Rakesh Giri where I felt safe and protected, or resting alone in my room (I moved rooms a lot, trying out seven different hotels in the area over the three weeks). I know Rakesh Giri was disappointed that I stopped sleeping there, but he understood when I explained that I needed alone time for my Sadhana (spiritual practice).

One of my dear friends sent me a voice message telling me about a dream that she’d had, in which I had long black dreads, everything was blue and shining and I was surrounded by people wearing really cool outfits. At first everything looked magical, but as she started looking closer at my companions, everything got darker and their faces morphed into demons. She told the message was clear- I had to stay alert and protect myself at all times, that not everything was what it seemed and I shouldn’t trust anyone.

I heard her worried warning and started taking more and more time for myself. One of the things I have learned over my years of nomadic living, is just how influenced I am by my environment.

Slowly, the energies around me seep in and things that were super strange at first eventually become the new normal.

When Rakesh Giri first told me to start wearing orange to affirm my new status as a Sadhu, I refused. Orange is not my color, and it felt fake to wear something just for show (call me a hypocrite if you want, while I love dressing up, this felt different). But then when I needed to buy new trousers to replace my broken pair, I found myself choosing an almost orange, mustard color, and not long after my transformation was complete as I got an orange dress, and gave into wearing the many shawls and scarves I was given in both saffron and red tones.

One day Rakesh Giri grabbed my dreads and tied them up ‘sadhu style’ and then took one of the cotton lungis from the big pile we had been given and wrapped it around my head, and after that I just started styling my hair that way myself. He gave me a rudraksha mala and told me to always wear it, and I did, even sleeping with it.

Again, to me the whole thing about wearing your spirituality feels somehow shallow, but it had a massive effect as peoples reaction to me change dramatically.

Now when I was roaming by myself, people greeted me with loud chants of “Har Har Mahadev” and moved out of my way, and many surreptitiously reached for my feet or tried to give me gifts as I passed by. I started getting every more donations, and other visiting Sadhus greeted me with ever deepening bows that showed I was worthy of respect. I guess I got used to that too, and to be honest, it made things easier for me, people treated me with a lot more reverence when I wore the ‘right’ colors.

It also made me realize just how important dressing the part is, to establish your place in the community. It makes it easy to spot the religion of all manner of priests, monks, nuns and Sadhus, because they have such distinct styles of fashion, dictating everything from style and colors of clothes to hair and beard styles. It is fundamental to all tribes to dress the same, and actually this new globalized fashion we are all wearing now, is both so basic and very boring in comparison.

Sitting in our spot at the base of the palace in Varanasi, I estimate that about an average of 700 people came into the tent each day. Sometimes it was so full of pushing and shoving bodies, that I felt claustrophobic.

Other times, especially in the evenings, when cooked chapati and vegetables cooked on the fire, it felt more like a happy family gathering.

One thing that I found hard to reckon with was how many people, foreigners and Indians alike would come to sit to talk to me and start bragging about their own Gurus and all their special powers.

I hope you’ll forgive me for this analogy but it feels quite appropriate to use with so many Naga Babas all around: it often felt like a dick-measuring contest “my guru has bigger balls than yours” kind of thing. All I can say about that is that it makes my bullshit radar go off, especially because what I came to admire the most about the Sadhus I felt drawn to was their absolute authenticity.

The longer I spent with Rakesh Giri, the more I realized that what I felt was a devotional love. From him and for him, mixed up in a way where I wasn’t sure which was which or whose came first or who it really belonged to. Sometimes I felt I cared more for his wellbeing and happiness than my own, but maybe that is also because he often took greater care looking after me than he did of himself.

Sometimes we argued, for example when my throat was so itchy I coughed until I vomited, then went to buy some soda because the cold tickles of the bubbles felt soothing in my throat. He tried to take it from me and shouted that in India you should only drink warm things when you are sick, and I shouted back that “My body is not Indian and where I come from, we drink cold drinks without problem”.

At times, he was right and I backed down, other times I refused and the arguments would end with him saying “You happy, I happy” and that would be the end of it.

Sometimes we giggled like little children, free from the burdens of being a ‘respectable adult’ masks we so often wear in modern society. Most of the time together we didn't talk to each other, we were just there sharing the energetic space and vibing off one another.

Whenever I closed my eyes and entered meditation, I immediately felt surrounded by a bright white light that I knew came from his force-field, and actually was a bit addictive.

After my initiation, he insisted that I introduce myself as “Maya Giri” from now on. It is also worth mentioning that while many people tell you that ‘Maya’ to means ‘illusion’, it really refers to this material realm, the dimension of matter, and so one interpretation is ‘wealth’ and ‘prosperity’.

Rakesh Giri made jokes about this often, and sometimes also me ‘Maya Laksmi’ because of how much people enjoyed giving me things and I guess how much that also added to his status. Being able to attract things is a big part rising in the Sadhu hierarchy. Part of the way you elevate your position is paying your way up.

While Sadhus don’t technically have jobs, they work very hard, starting off in service to their Guru, obediently doing everything asked of them.

But even the Gurus are doing so much - seeing Rakesh Giri sitting from dawn til early morning hours patiently giving blessings, sage counsel and fighting hard to keep his space clean both physically and energetically, as well as all the tapasvi and austerities he practices up in the Himalayas between Kumba Melas, it is impossible to call a sitting Sadhu lazy.

(Rakesh Giri Baba as Naga Baba sweeping the area of his tent)

It is their energy that attracts people and things to them, and so these lessons in sitting down and letting things come rather than running around chasing (which is what you do to get rid of bad energy as they demonstrated) are profound wisdom teachings that I technically knew before, but had never experienced so fully embodied until I sat with the Sadhus for these six weeks and saw with my own eyes what actually manifested as a result of their trust and patience.

After our month in Varanasi the space under the yellow tarp had become something of a cluttered and messy open-air living room, overflowing with so much stuff, a testament and proof of the ‘let things come to you’ philosophy put into practice.

Some things were deemed worth taking to Tungnath, other things were left behind just as unceremoniously he’d walked away from his mega tent in Prayagraj.

I haven’t mentioned him, although he was a steady companion during our month in Varanasi, the mostly quiet, very old (and totally toothless) Baba who sat and slept next to Rakesh Giri. I grew to love him too, even though we rarely spoke during our month of sitting together, he held this gentle loving constant presence next to us by the sacred fire. Every so often, he would hand over a bundle of 500 rupee notes to Rakesh Giri, and I have no idea where he got them. When we said good-bye, he did as so many other Sadhus and asked me to save my number into his phone. He and Rakesh Giri just nodded their heads to each other before we left, which I found strange after sitting, eating and sleeping side by side for a month.

As we set off for Rishikesh, the intention was to spend a few days there waiting for the ice to melt on the Himalayan roads so we could travel up to Tungnath, which I was really looking forward to. I wanted to finally visit the cave where my Guru lives, and see the wild leopard that often comes to sit with him as his meditation companion.

After three days at the peaceful homestay on the mountain side, I got violently ill again. This time, my mind caved in completely, and became a very dark place, full of negativity, fears and depressed thoughts. Rakesh told me contemptuously “you have a weak mind” and said he didn’t want me around. I had the shits and projectile vomits, high fever, weak and totally delirious, I was left to cry in alone in my room. He did make sure I got medicine and drank water, but I admit, I wasn’t pleasant to be around, in fact I felt I was dying to get away from my self at this point.

As I mentioned in the beginning of my story, I was becoming increasingly anxious, and started questioning the whole thing, and what kind of God would want me to endure this self-imposed suffering like the Sadhus advocate.

When I was a little girl, the word ‘stark’ (the word for 'strong' in Swedish) became my mantra of affirmation before I even knew what that was. Being strong has been one of the most identifying features of who I shaped myself into as a result in this lifetime. It was a survival response to deal with the family and situation I was born into. I don’t have any illusions of being special, if anything my personal flavor of problems and pain is what makes me human.

All the ancient spiritual teachings speak plainly of the ‘suffering of life’ and the goal of Hinduism, the reason the Sadhus follow the path of Sanatan Dharma, is to break free from the wheel of reincarnation in this realm of suffering, and the goal of it all is spiritual liberation.

Now, coming to terms with the fact that I wasn’t strong enough to live the Sadhu life anymore shattered those parts of my self that identified as the ‘strong’ one, that I have held onto for dear life as long as I can remember, and I felt weak and pathetic.

In my meditation, these words came with total clarity:

“There is no shame in choosing a soft life”

and with those words, something deep inside me finally broke, and in that breaking, I broke free.

This is not my life. My life is not this. I wasn’t made for this. This is not who I am.

I am free. It is time to go live another reality. My life is what I chose to make of it.

While still feverish, and squinting at the light of my screen, I booked tickets to from Dehradun to Delhi and then to Bali, the island of Gods, where I felt called to, where life is so much softer and sweeter than the hardships of Northern India.

At first Rakesh Giri simply said “good” and then ignored me when I told him of my plans. It hurt, but it was nothing compared to the pain of admitting defeat, of being confronted with the reality that I wasn’t strong enough to endure anymore.

When I started to feel better, which I think had a lot to with having made the decision to leave, and accepted that our time together was coming to an end, we had a nice day celebrating my 41st birthday with a visit to a special Shiva temple, pouring water down a silver yoni onto a small black stone inside a hollow in the floor, a special ‘shiva lingam’. People queued up for hours to get their chance to do this, but me and Rakesh Giri were escorted by the temple keepers, past all the patient pilgrims and were in and out of the temple in less than five minutes. We ended my birthday eating veggie burgers from Burger King (the only food I trusted to be clean enough for my now very sensitive stomach) and super fancy chocolate cake from the best bakery in Rishikesh.

(Rakesh Giri meditating in a cave in Rishikesh)

That last evening before leaving (my taxi was booked for the airport at five in the morning), we sat together on the terrace. My heart was hurting in a way I have never experienced.

This man, this free, wild, crazy, man, who had kept me safe, looked after me to the very best of his ability, protected me, fed me, now asking if I needed money, tried to give me even more of from his rather large jewelry collection (I left with one of the silver rings he had on his penis, a silver necklace and a fancy watch) but refused his offers of charras, explaining that a) I didn't want to smoke so much anymore, and b) it wouldn’t be possible to get it through airport security anyway.

“Anything you need, you ask, I give you, no problem” he said over and over again.

I’ll be the first to admit, its strange, but I have never felt so much love or been so totally devoted to another person.

We both cried saying goodbye, and my heart pounding and aching as I turned away from him and left.

As I write this, it has now been two weeks since I left Rishikesh and waved goodbye to my Guru on the mountain.

Arriving in Bali, all the anxiety and heaviness started to disappear from my system. The first two days here, I didn’t leave my room, I felt so peopled-out I just needed to be alone in my own space. Then slowly, I started to come out again, feeling like the a bud blossoming into a new, rawer and more real version of myself.

I have been meeting and connecting with beautiful individuals, both old friends and new, and inside of me I am more peaceful and feel more powerful, but also more attuned to the shared suffering and sadness of our collective humanity than ever.

I am sorry that I didn’t make it all the way to Tungnath, and I am still figuring out the effects these experiences have had on me. I am still alive, and my energy levels are back, I feel an even deeper reverence for my body, and more peace in my soul than I’ve ever know before.

Maybe one day I’ll return, and complete the pilgrimage to the highest Shiva temple in the world, to sit at the feet of my (now four-toothed) Guru, meet his wild pet leopard and see the ashram he’s building where he told me I am always welcome and where I have a room waiting for me anytime.

(Rakesh Giri waiting for me to come out of the meditation cave)

And so for now, my journey continues, and while there are still so many stories left untold, parts of my heart will forever be with him, because somehow, while we are worlds apart and so fundamentally different, there is something in us that is the same.

That spark, that twinkle of something that I will never find the right words for, utterly undeniable in its force that can only be felt through first-hand experience.

There are three things you must do for your Guru:

Find Him √

Love Him √

Leave Him √

(meditating inside a tent at the Kumba Mela)

This is not where my story ends.

Thank you for coming on this adventure with me, I am beyond grateful for your gracious feedback and all your supportive and encouraging comments.

This time and all what I experienced have affected me in ways that I am still discovering and digesting. Writing these stories has been one way for me to process, and returning to my love for words and writing is only one of the many gifts I've received after leaving to come back to my self.

I am both softer inside and sharper around the edges than who I was when I went.

Ultimately I am left with a deep gratitude for everything I’ve lived through, and amazed that I lived to tell the tale, but in answer to your question of ‘will I go to the next Kumba Mela in 2037’, right now I am pretty sure this really was a ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ kind of experience. But who knows, only time will tell.

With the growing population of India, the forecast is that over a billion humans will attend the 2037 Maha Kumb. I don't know who I’ll be by then, but I do have the most utmost respect and admiration for all the people who came together and made the biggest spiritual gathering in the world happen.

If you are considering making the journey yourself, please do let me know and I’ll help you get prepared and put you in contact with the people who I now consider as some of my realest friends.